When I was nine years old, my parents took me to France. Among many other cultural and historical sites we visited, we viewed the cave paintings at Lascaux, not long before they were closed to the public forever.

Although the identity and motivation of prehistoric artists is lost to us, their anonymity allows us to enter into a direct relationship with their art uncomplicated by biography. By contrast, it is extremely difficult for us to evaluate the work of a Van Gogh or a Hemingway unaffected by the facts we know about their lives.

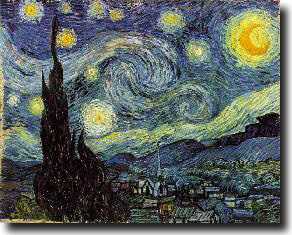

Imagine that Van Gogh's Starry Night was discovered, like the Lascaux paintings, on the wall of a cave, and that we knew nothing about the artist himself, not even his name. The work alone, with our field of perception now narrowed to its four corners, would make a powerful impression--and would also communicate some salient facts about the artist's mental state.

Similarly, the delicacy of the Lascaux paintings, their realism and attention to detail, the grace of the animals portrayed, allow us to imagine a human being with intelligence, judgment, a powerful sense of the beauty of the surrounding world, and complete control over the medium. Yet we do not know the artist's gender, language, motive for creating the work, or daily life.

We can only speculate as to whether there was any commercial motive in the creation of the work. Money almost certainly did not exist. Though it is possible the artist traded art for food, most art history and anthropology texts communicate that art began with religion and only later became commerce. A common explanation of cave paintings of animals is that they were intended to bring the tribe luck in killing the real life exemplars of those same animals.

This opens an interesting line of inquiry. Magic and religion don't always require the accuracy, or delicacy, of the Lascaux cave paintings. Just as two twisted branches tied together can represent a cross, a barely legible four legged figure scratched in the stone might be enough for sympathetic magic. The Lascaux artist paid more attention to detail, had more of a command, than the sculptors of primitive earth goddesses (often just several round lumps of clay smeared together) or early Christian painters. He or she was a better artist than they. Why?

If we attempt an evolutionary explanation for art, we must answer the question what art did to ensure the artist's survival. Of course, it is possible to imagine an answer to this: if art served a religious or aesthetic need of the rest of the group, even before commerce began it might ensure that the artist was better fed than other people---and that the best artist was better fed than other artists.

Though this has undoubtedly been true of some artists at some times, it is contradicted by the familiar type of the "starving artist." Certainly, in the last few centuries (coinciding with the time when biography became an accepted form and we began to know the details of artists' lives), a human being, by becoming an artist, placed himself initially on the margins of society, rather than securely at its mainstream. Art as a survival mechanism would dictate giving the public exactly what it wants to consume, nothing more; though many artists have always done this, it is recognized that a primary role of the artist is to lead taste, not to follow it. The miserable, misunderstood Impressionist painter described by Zola in L'Oeuvre, with his lurid canvas of a dead child mocked and reviled by the critics, is a nice fictional embodiment of the dialectic between artist and public.

Evolutionary theory gives another possible explanation for art: perhaps it is a spandrel, an accidental byproduct of other qualities that were selected for, such as a larger brain, the capacity to think abstractly, and better hand-eye coordination. Art then becomes an exercise in utilizing excess capacity, the way play discharges energy. This parallel is especially interesting, because the line between art and play is not always precise (cf. Huizinga's Homo Ludens, "man the player").

On the island of St. John's, there is a beautiful trail that runs from the island's only highway to the ocean on the north side. Two thirds of the way down, you cross a pool of fresh water. Petroglyphs resembling octopi and rams' heads have been carved in the rock around it. They have been there at least four hundred years, and no-one knows who made them or what they represent.

I imagine that an Arawak or Taino cooled himself (or herself) in the pool on a hot afternoon four centuries ago and passed the time by scratching the images with a rock. Unlike the Lascaux artist, who may have been painting for the tribe, the small pool in the woods on St. Johns and the informal and hurried look of the petroglyphs suggest a solitary artist who was doodling. If so, you have the spandrel theory in full glory: the petroglyph maker was not earning his bread, or acting to impress others. I would like to imagine that he was closing a loop with himself, satisfying a private need, as we all do when we doodle on a pad.

He may not have thought of what he was doing as art, either. But it is not strictly necessary to a theory of art that the creator understand himself to be an artist; we define art by its impact on the viewer, rather than by the intention of the maker. It is impossible for us to know if the Lascaux painter had any set understanding of art as an activity, either. Even in the case of more recent artists on whom we have more information, we can question whether Shakespeare thought of himself primarily as an artist, and we can point to twentieth century writers such as Philip K. Dick who were "accidental angels", setting out to create pulp fiction and making art along the way.

There are four possible motives for making art: to satisfy a personal need, to honor God, to achieve public fame, and to make money (of course, these four can overlap each other, especially the last two.)

The second motive, honoring God, is not frequently found today, but was a significant motivation for much art of the early Christian era up through the Renaissance. It is doubtless the main motive of much anonymous art of the Middle Ages where the artist apparently sought no public reputation.

Each of the last two motives, fame and money, is not likely in itself to provide a complete explanation of any art that is remembered centuries later. Postulate an individual with exceptional control over his hands and a fine, discriminating aesthetic sense. If solely motivated by a desire for acclaim and financial reward, he would be motivated to take no risks whatever, but to deliver to the public an exact replica of whatever it already had applauded and paid for. Such an artist today would be drawn to create kitsch more readily than art. Thus we must look beyond a mere desire for fame or money in understanding an artist who leads taste, who pursues something difficult and makes it popular. And we are all familiar with cases of artists, like Zola's fictional Impressionist, or Van Gogh or Kafka, whose work did not find widespread acceptance until after their death.

To explain the phenomenon of seeking the unpopular and difficult, we must resort back to the personal motive. Even when such artists become popular and rich, they have been favored by the conjunction of the personal and public motives. First, the artist closed a loop with himself; because of favorable circumstances, the same artistic act later proved to close a loop with the public as well. The artist's need foreshadowed, or created, a public need as well. Obviously, the public must meet the artist halfway. Just as the world was not ready for the steam engine when an ancient writer described one, the artistic discoveries of the Renaissance fell into a fertile soil which did not exist a century or two earlier. It is very likely that many successful artistic innovations are not novel at all, but when tried earlier met such complete incomprehension that they have failed to enter the historical record.

If the personal motive exists in all remembered art, it is likely that it lies deeper than, and exists independent of, the desire for fame or money. The artist is driven to close a loop with himself, repeatedly, for years on end, irrespective of whether it serves his other goals. It is this private and continuing act of dedication which drives the artist to be successful. If it did not exist, no artist would ever survive a long apprenticeship before success, and none would be revealed to have a rich, creative private life. The notebooks of Michaelangelo and Da Vinci establish how small a percentage of their total attention was required the commercial side of their enterprise.

Of course, money and art are so intertwined today it is all but impossible to consider them separately. While the Lascaux artist undoubtedly went out and gathered his materials, then made pigments from them, an artist today typically must purchase his materials and also looks to support himself, now or later, by making a living from his art.

While the life of the individual artist recapitulates the life of the race---a certain amount of physical comfort and free time is a prerequisite for art---beyond a certain point, money counters art, rather than promoting it.

When the desire for money becomes predominant over the personal motive, bad art frequently results. Many commercially successful artists end up working too much but not creatively enough. Late Picasso ceramics, screenplays by Raymond Chandler or William Faulkner, the xxth novel by a writer whose talent dried up decades ago. When a J.D. Salinger, Henry Roth, Harper Lee or Ralph Ellison writes a strong novel, then is not heard from again for decades, we suspect writers' block or some other pathology--- but the explanation may simply be that the artist has successfully closed the loop for once and for all and is refraining from delivering more work of inferior quality.

At the live concert captured on her album Miles of Aisles, Joni Mitchell complained that no-one ever told Van Gogh, "Paint Starry Night again, man," while singer-songwriters are stalked by requests to recreate their earlier hits forever. She was wrong, as is proven by the late careers of many artists who began by pursuing the personal motive and ended by creating factories for the mass production of their most popular work. If Van Gogh had lived long enough to become financially successful, he might in fact have painted Starry Night over and over again.

At this point, the personal motive is completely submerged in the financial one and the artist takes no new risks, but continuously seeks to replicate earlier successes. A new species of kitsch is created.

At the extreme end of this spectrum are hundred million dollar Hollywood movies, which have so much money invested in them that their creators can take no risks whatever. Such movies can only retail to the public the same thing it paid millions of dollars to see last year. The inflation in Hollywood spending paradoxically explains the remarkable success in recent years of independent films, some made for as little as $7,000.00. The less money, the greater likelihood of art.

As for fame, it is unlikely that either the Lascaux painter or the St. John's petroglyph artist had any conception of it, at least in the sense of a reputation lasting longer than a lifetime. The petroglyph artist may not even have thought about the possibility of anyone else seeing his work.

A desire for immortality, because its realization depends on so many circumstances outside one's personal control, tends to signal a highly immature and self-deluded personality. Only assassins are assured having their names enter into history based upon a single act. Artists face a difficult apprenticeship which in many cases lasts an entire lifetime, with elusive fame coming afterwards or not at all. Again, the personal motive must be very strong to motivate an artist to do the work necessary to have the least chance of winning the reputation.

What is the personal motive? Frequently the artist himself would be unable to explain it. Anyone who has ever watched an artist sketching knows that something is communicated from the unconscious mind directly to the hand without passing through the forebrain. At this level, sketching looks like a direct discharge of nervous energy---which we all know doodling, a type of sketching, to be. You might as well ask a child, or a young animal, why it enjoys play.

While the critical activity may attempt to explain the conscious and unconscious strains of thought expressed in Crime and Punishment, there is no process of reconstruction which would allow us definitively to answer questions such as why Dostoyevsky placed Svidragailov in the novel--a character who may himself be a murderer, and who commits suicide. What exactly Svidrigailov is is never confirmed; his inner identity lies on the other side of Dostoyevsky's event horizon, like the process which created him.

Like the mind itself, the art-making process can be modelled in evolutionary or neurological terms, but it continues to elude explanation.

Most artists are uncomfortable describing the origins of their ideas---there are remarkably boring essays "On the Novel" by E.M. Forster and Edith Wharton, for example, in which they never discuss their own work. Perhaps artists feel that explaining the genesis of a story or a picture will decrease its mystery, by exposing the machinery. One exception was William Butler Yeats, this century's greatest English poet, whose interest in symbolism and the unconscious mind led him to consider the artistic process in a number of his poems. In "Fragments", he asked:

Where got I that truth?

Out of a medium's mouth,

Out of nothing it came,

Out of the forest loam,

Out of dark night where lay

The crowns of Nineveh.

In "Long-Legged Fly", he describes Caesar thinking in his tent, Helen daydreaming, and Michelangelo on his scaffold, following each with the same refrain:

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream,

His mind moves upon silence.

Finally, at greatest length, in "The Circus Animals' Desertion", he portrays the failure of creativity in old age. The final stanza:

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind, but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder's gone,

I must lie down where all the ladders start,

In the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart.